7.1 Review Goal-Setting

At this stage of a project, when the 3D models have been produced, documented, and archived locally, there is a natural break in activity, which presents an opportunity to review the goals that have been previously set for your project.

Digitization projects can take a long time to complete and new examples of dissemination best practice may be available, or even new software, services, or platforms may have sprung up that best serve your project goals. It is at this stage that you should look outside of your organization and review the best ways to reach your identified audience(s).

7.2 Publish as Interactive 3D for Browsing Audiences

As described in the “What is a 3D Model?” section, for a user to truly experience a digital 3D model, the model needs to be interactive. At a very basic level, this means a user must be able to turn or tumble a 3D model to view the model from different angles and zoom in and out to get a closer look or broader overview of the resource. While this was previously only possible via dedicated applications running on specialized hardware, thanks to modern web standards like WebGL, it is possible to offer proper 3D interactive experiences in any modern browser. That means the model is accessible to all users, even those without the technical expertise to use their own 3D modeling software.

Ongoing technical developments—for example, in the smartphone and head-mounted display industries—make it easier than ever to offer different kinds of 3D model-based experiences. 3D models can be manipulated on screen via a mouse and keyboard or a touchscreen interface, as well as via the more physically engaging interactions of virtual and augmented reality.

Publishing a 3D model of a cultural resource without any context is unlikely to be of particular use to your audience. Thankfully, as with most other web-based content, 3D can be published alongside other information (e.g., text, images, video, audio) in a web page, which will likely go some way to satisfying your digitization project goals.

A step further is to embed contextual and descriptive information within the 3D viewer itself in the form of 3D annotations—that is to say, hotspots or points of information attached directly to the surface of a 3D model. When clicked or tapped, these hotspots display or play back information, most likely related to the point or area on the 3D model to which they are attached.

In this manner, it is possible to create interactive 3D tours of digitized cultural resources as a proxy for in-gallery experiences like guided object handling.

Numbered annotations make it easy to draw attention to specific places in the model. Ancient Maya plate for chocolates by Alexandre Tokovinine, CC BY 4.0

7.2.1 Notes on Digital Display

The same 3D model can generally be displayed using different 3D viewing software (often referred to as a 3D viewer). 3D viewing software is different from 3D editing software (often referred to as a 3D editor) in that the primary purpose or functionality is to simply display 3D data on screen as opposed to editing or converting it in any significant way.

Each software reads the 3D data file(s) and displays it as pixels on the screen—this is known as rendering. The part of a software that calculates what the digital file should look like on screen is known as a rendering engine. Different rendering engines support different file types and file-specific data. As a result, the same 3D file can look very different in different 3D viewers. That means you will be making choices about how people view the files you create, not just how you will create them.

Baluster vase, from a five-piece graniture rendered in the Smithsonian Institution’s Voyager 3D viewer

Baluster vase, from a five-piece graniture rendered in the Sketchfab 3D viewer

7.2.2 Choosing an Online 3D Viewer

Deciding on which 3D viewer you use to display your 3D models online will largely depend on your project goals, your organization’s policies for using third-party platforms, and capacity for ongoing technical support and development.

7.2.2.1 Self-Hosted Storage and Display Solutions

Self storage and hosting can offer greater control over how our 3D models are presented (e.g., custom interfaces) and how people interact with and access them (e.g., only via your organization’s website).1 These benefits come at the expense of maintaining web servers and application code.

7.2.2.2 Hosted Storage and Display Solutions

Using a hosted 3D viewer service is the quickest route to interactive online publication for your 3D data. Generally, using a hosted 3D viewer will require uploading your data to third-party-owned web servers and agreement to platform-specific terms of use. Benefits of using a hosted storage and display solution include reduced technical and staff overheads for you and your organization, and dissemination of your 3D models to an existing, 3D literate community.

7.3 Publish the 3D Data for Download

Publishing a cultural resource as an interactive 3D model goes a long way to making 3D models findable and accessible. The next step is to make the 3D data available for download (hopefully alongside an interactive viewing experience). Published 3D data should be in an interoperable format—i.e., a 3D file that can be opened and edited in a piece of software. Publishing 3D data in an inaccessible format—for example, as a downloadable 3D PDF or self-contained app—is essentially a dead end for data re-use.

The simplest way to make data available for download is as a .zip archive hosted somewhere online. Whatever files are offered for download, it should be made clear what the data represents, what format it is in, and what license it is being offered under, prior to the download being initiated. Additionally, it is good practice to include this information in the download archive itself as a plain text file.

Publishing 3D data for download assumes some level of skill in the target audience regarding 3D. The “data package” approach mentioned previously will go a long way to making your published data attractive to a given audience. Where necessary, you should consider guiding audiences to recommended software and activities that match the data you are offering.

Finally, keep in mind the difference between a “self-serve” approach and a managed approach to download.

“Self-serve” means that anyone may easily download and save 3D data locally without contacting the publisher, although the end user may be required to sign in or up to a service to enable this ability. This is the most accessible and fastest route for someone to receive your 3D data.

A managed approach in which an end user must, for example, request 3D data via email or webform and wait for a reply each time they wish to make a download, would not be considered best practice for open access. Gatekeeping practices will deter potential users, who will ultimately go elsewhere for 3D content that is unrestricted. Your organization should prioritize and implement analytics tools to track downloads for institutional reporting and to measure engagement, but not at the social capital cost of turning away your users.

7.4 Publish Derivative Content

Publishing images, animations, and video derived from 3D models can be a helpful complement to the 3D data or viewer itself. Using media and media platforms that audiences are more familiar with can be an enticing gateway to engaging with the 3D data itself. Some examples:

High-Resolution Image Renders

King Gustav Vasa’s Helmet with a Gilt Crown by The Royal Armoury (Livrustkammaren), CC BY 4.0

360 “Turntable” Animated GIFs

Screen Capture Video Exploring a 3D Model

Remixes

3D models produced by institutions can find their way into remixes and new forms of cultural production outside their own media creation. These creations can take any number of forms, including movies.

Lucio Arese produced a computer graphic imagery movie Les Dieux Changeants using 3D Models, done by Jonathan Beck and the Scan the World initiative, of plaster casts from The National Gallery of Denmark (Statens Museum for Kunst; SMK) on MyMiniFactory. This is an example of a remix of institutionally sourced 3D scans that have been used to make a new and thoughtful work.

7.5 Availability and Findability

Publishing the 3D data online in any form does not signify the end of an Open Access digitization project. An element of promotion and making the invitation to re-use 3D data clear to target audiences is essential to increase engagement with any Open Access program. Some select considerations for publishing your 3D outputs are laid out below. For guidelines to improve the findability, accessibility, interoperability, and re-use of any kind of digital assets, consider reviewing the FAIR Principles.

7.5.1 SEO

Good search engine optimization (SEO) of web pages featuring your 3D models will help people discover your project online. If somebody performs a web search for “[your organization name] Open Access” or “[term related to cultural resource] 3D model” (as two basic examples), they should be pointed in the right direction.

7.5.2 Data Interfaces/APIs

Making your data available via both human and machine interfaces—that is to say browsable web pages as well as APIs—allows for different forms of engagement. The former caters to individuals and individuals presenting your work to a group (e.g., teachers presenting to a classroom of students); the latter can plug your cultural 3D data into entire digital platforms and get it in front of potentially massive 3D-oriented communities.

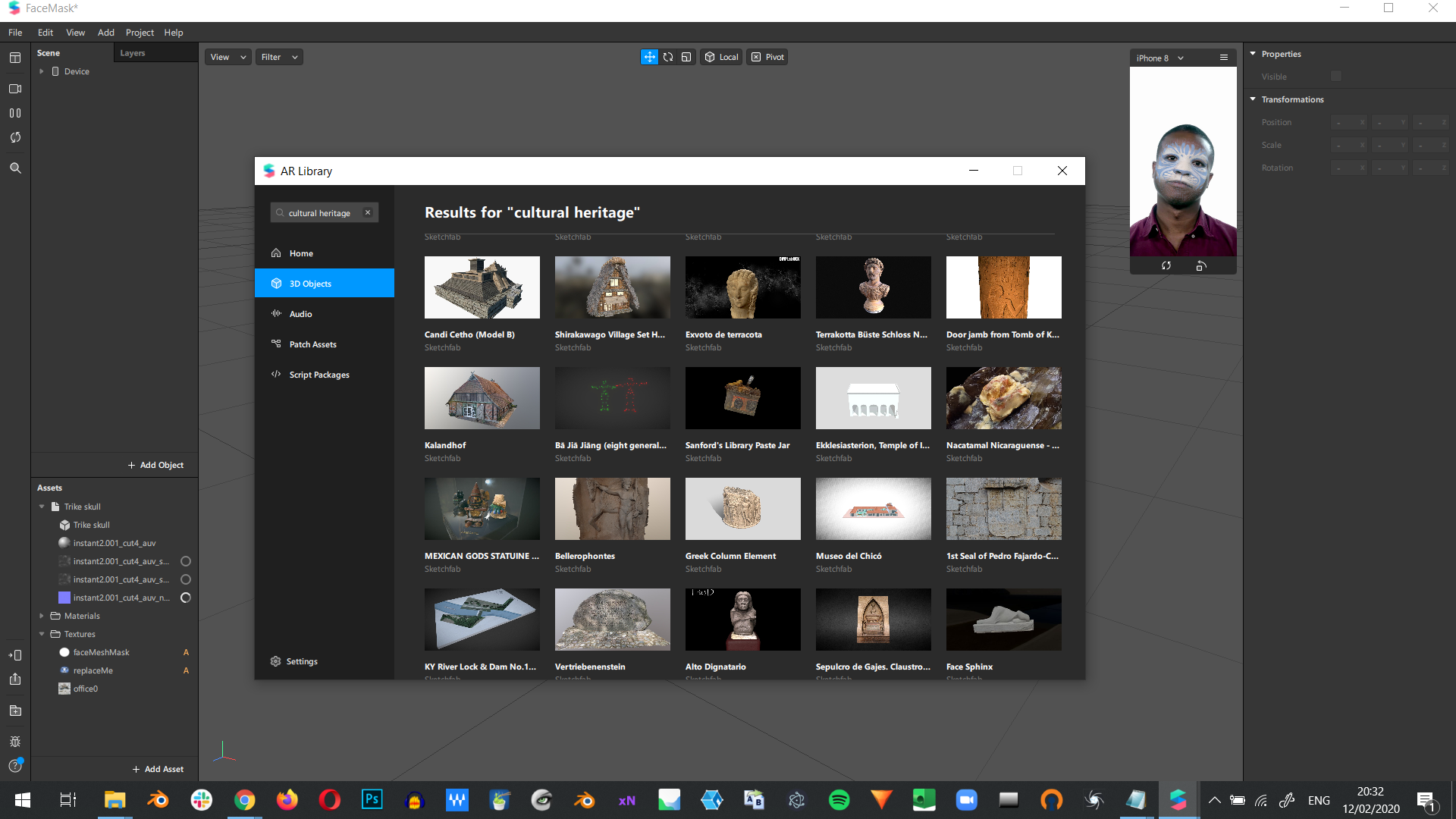

Browsing 3D models hosted on sketchfab.com in Facebook’s Spark AR application (used to make Instagram AR filters) is made possible by an API integration.

Smithsonian Institution’s Open Access Developer Tools

7.6 Active Promotion

Once 3D data has been published, it should be a priority to advocate for its re-use by colleagues within your GLAM organization as much as by your target audiences. Teach people how 3D models can be embedded in object collection pages, exhibition marketing, in-gallery interactive—wherever it’s relevant. Make a special effort to support marketing and social media teams in understanding how they can draw on 3D model resources to create engaging content tailored for audiences where they already exist—i.e., digital newsletters, blog articles, and social media platforms.

7.6.1 Partnerships

Any strategy for disseminating 3D content online should define basic partner platforms to help deliver the same 3D content in as many ways as possible. Different online platforms offer varying functionality and often cater to specific audiences and choosing the right platforms.

The practicalities of posting the same 3D models on multiple platforms necessitate ongoing additional staff time or a one-time investment in building an automated workflow.

Some platforms to consider:

-

Google Poly - “Explore the world of 3D.”

-

Morphosource - “MorphoSource is a project-based data archive that allows researchers to store and organize, share, and distribute their own 3d data.”

-

Mozilla Hubs - “Share a virtual room with friends. Watch videos, play with 3D objects, or just hang out.”

-

My Mini Factory/Scan the World - “Enabling a decentralized ecosystem for 3D creatives, one step at a time.”

- Sketchfab - “Sketchfab is empowering a new era of creativity by making it easy for anyone to publish and find 3D content online.”

-

Thingiverse - “MakerBot’s Thingiverse is a thriving design community for discovering, making, and sharing 3D printable things.”

- Wikimedia Commons - “We’ve enabled a new feature that allows you to upload three-dimensional (3D) models.”

7.7 Legal Infrastructure

It is critical to include legal information about digitized cultural assets to users. Without this information, users will be unable to make full use of digitized assets.

7.7.1 Licensing Best Practices (Digitizations of Cultural Objects)

As described in Section 5.3, many jurisdictions do not—or soon may not—recognize an additional copyright interest in digitizations. As a result, in many cases—although certainly not all—digitizing institutions will not have a copyright interest in the digital file that represents a cultural object. In light of this ambiguity, institutions should use licenses to clarify how users may make use of files included in Open Access initiatives.2

7.7.1.1 Legal Agreements

The current best practice is to use the Creative Commons CC0 mark on all Open Access digitized objects. The CC0 mark is designed to waive any copyright interest jurisdictions may grant your institution in the digitizations themselves. This includes the jurisdiction where your institution is based, as well as jurisdictions where your user may be based. Using the CC0 mark makes it clear to all users that the digitizing institution does not claim additional legal rights in a digitized object in the relatively unlikely event that those rights do exist.

Note that using the CC0 mark does not require your institution to warrant that the digitized cultural resource itself is in the public domain.3 The CC0 mark merely indicates that the digitizing party will not claim additional ownership or control over the file. To the extent that the digitizing institution has additional information about the copyright status of the cultural object, RightsStatement.org provides standardized ways to describe that status outside the bounds of formal legal tools.

It is not currently considered best practice to place attribution, non-commercial, or educational-use-only restrictions on digitized cultural resources.4 These restrictions can be hard for users to interpret consistently and may unintentionally discourage the types of uses you hope to encourage. It is also likely that copyright-based use restrictions placed on public domain works are not enforceable, further complicating the legal status of the files and discouraging use.

While it is best practice for an institution to share provenance information about a cultural resource, it is acceptable for a digitizing institution to include a disclaimer that the provenance information provided may not be accurate or complete, and that users should not necessarily rely on it when making rights status determinations. A disclaimer can be used to indicate that the institution is making the works available for “all legal purposes” or “any legal purpose,” which may address concerns about edge cases where bad-faith users could make use of the works in a way that violates specific laws.

Institutions should also avoid the impulse to impose additional restrictions on users via terms and conditions attached to a distribution platform or even individual files. These types of restrictions complicate downstream uses because it can be hard to determine if any individual user is legally bound by them. Similarly, these types of restrictions may create unreasonable—and unenforceable—expectations about the type of control your institution will have on the use of the files.

7.7.1.2 Non-Legal Indicators

While it is not best practice to impose legal restrictions on the use of digitized cultural resources, it is acceptable to make non-binding requests of those users. This is especially true in the case of restrictions—such as a requirement of attribution—that the institution is unlikely to actively enforce through legal mechanisms. It is critical that the institution makes it clear that it understands these requests to be non-binding, and not to cloak them in quasi-legal language or presentation styles.

For example, institutions can request that users use a standardized way to communicate the source of the digitized cultural resource to others. They can also provide an easy way for users to report their use back to the institution. Although these requests are not legally enforceable, many users will happily comply with these types of requests from digitizing institutions.

These best practices have generally been developed for cultural resources in the public domain. If you have digitized cultural resources that are protected by copyright, best practice is to clearly communicate the terms of that agreement with any users as thoroughly as possible.5

7.7.2 Licensing Best Practices (Metadata and Descriptions)

Section 5.3 explains that digitizing institutions may have more legal rights in information such as metadata and descriptions of digitized cultural resources than digitized versions of the cultural resources themselves. Nonetheless, it is best practice for digitizing institutions to license all metadata and descriptions using the CC0 license.

Other permissive licensing structures (such as the attribution requirement of a CC BY license) can create unintended challenges for downstream users of metadata and descriptions. Metadata and descriptions will often be used in large-scale analysis or other data-driven investigations. Determining the proper way to comply with even a seemingly straightforward attribution requirement in a CC BY license can present disproportionate challenges to users, discouraging the types of uses you may hope to encourage.

As with the digitized cultural resources themselves, nothing in the use of CC0 prevents the digitizing institution from requesting attribution or feedback on re-use. The difference between a request and a legally binding demand increases the amount of flexibility available to the user.

7.7.3 Presenting Legal and Quasi-Legal Language

Institutions should strive to present legal and legal-adjacent information in as approachable a manner as possible, and to streamline its presentation to the public. While licenses, warranties, and requests are important, they can also be intimidating to users without a background in legal text. The mere presence of “legalese” can act as a barrier for perfectly legitimate uses. Successful Open Access projects are inviting to users. While it may feel like adding one additional clause to address an edge case is responsible stewardship or lawyering, the cost of doing so may be reducing the types of engagement that motivate the initiative in the first place.

In contrast to additional legal language, a clearly and concisely written values statement can help institutions articulate the role and position of an open access program in the holistic context of the organization. Value statements should be affirmative, considerate, and action-orientated, without taking a discouraging or scolding tone towards users.6

7.7.4 Cultural Labels and Notices

Many cultural resources have other considerations or cultural restrictions that are important to communicate to users. While these considerations and restrictions may not be legally binding, many users will benefit from being aware of them. Communities and stakeholders may also be more supportive of digitization and dissemination efforts when they are accompanied by this type of information.

Local Contexts’ Traditional Knowledge labels help to facilitate the communication of these types of non-legal use considerations. The labels give cultures that created the works a way to clearly communicate important context to users. They also give users a straightforward way to identify these restrictions and incorporate them into their application. Cultural Institution Notices, also developed by Local Contexts, are specifically designed to be used by cultural institutions as they engage in collaborative partnerships with communities to address problematic histories, unclear provenance and incomplete attribution.

NEXT SECTION Evaluate and Join

Notes

-

The IIIF 3D Community Group maintains a more extended comparison table of these and other online 3D viewers. IIIF 3D Viewer Functionality Matrix, IIIF Google Document, https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/ d/1mZFF1kgEfjqN1MC_ Ds0LQyxPvzUUXSHJLksn-uTvtdQ/ edit?usp=sharing, last accessed April 16, 2020. ↩

-

Nick Butler has created a helpful guide for navigating copyright for digital GLAM institutions based in New Zealand. Copyright for digital GLAMs: Lessons from NDF2019, Nick Butler, https://www.boost.co.nz/blog /2020/01/ copyright-for-digital-glams-ndf2019 (January 21, 2020). ↩

-

The Creative Commons Public Domain Mark may be appropriate if your institution has positively identified a work to be in the public domain. See Public Domain Mark 1.0, Creative Commons, https://creativecommons.org/ publicdomain/mark/1.0/, last accessed April 16, 2020. ↩

-

For example, while the UK’s National Lottery Heritage Fund generally requires grantees to use a Creative Commons Attribution license on funded work, it explicitly informs grantees that “[d]igital reproductions of public domain materials, including photographic images and 3D data, should be shared under a CC0 1.0 Public Domain Dedication.” Advice: Understanding our licence requirement, The National Lottery Heritage Fund, https://www.heritagefund.org.uk/ stories/advice-understanding- our-licence-requirement, last accessed September 16, 2020. ↩

-

Rightsstatements.org provides 12 standardized rights statements, each with a unique URI and accompanying text, to help with this process. ↩

-

See Open Access Initiative Values, Smithsonian Institution, https://www.si.edu/ openaccess/values, last accessed July 7, 2020. ↩