i. Leading Examples of 3D Models and Open Access

The following organizations are leading examples of 3D models and Open Access of cultural resources.

i.i The Cleveland Museum of Art (CMA)

The Cleveland Museum of Art went Open Access in January 20201 with the Open Access release of data and 2D images. CMA hosts an online dashboard that publicly reports engagement metrics on its open access program. Its policy also enables others to create their own 3D scans of public domain collections at the institution within certain conditions.2 CMA subsequently scanned and made available 3D images in partnership with Sketchfab on its platform and via the museum’s website using the Creative Commons Zero Public Domain Dedication for cultural resource items in the public domain.3 CMA was one of the first museums to make 3D models available on a museum website and use the Creative Commons Zero Public Domain Dedication. CMA continues to add openly licensed 3D models to its online collection.

i.ii The National Gallery of Denmark (Statens Museum for Kunst; SMK)

The National Gallery of Denmark (SMK) has been a pivotal leader in the international Open Access movement since 2016. Lead by Senior Advisor and Curator of Digital Museum Practice Merete Sanderhoff, with Head of Digital Jonas Heide Smith, the SMK Open program has produced important philosophical position statements through its blog, co-sponsored the “Sharing Is Caring” conference series4 that introduced innovative prototypes and new products, and continued to progress consistently with its ongoing rigorous commitment to Open Access. SMK has made significant contributions to the 3D imaging space as well, with its digital cast collection5 and partnerships with initiatives like Scan the World6 and MyMiniFactory.7 SMK partners with Sketchfab8 also to provide access to 3D images. 3D models of sculpture were also made available to explore on mobile devices in augmented reality.9

The ethos of SMK’s efforts with Open Access and its 3D images are defined by “radical openness” and it views cultural resource items as building blocks for making new culture:

SMK breaks away from the idea that museums should create all content themselves. SMK Open provides access to art, essentially offering it up as building blocks. Then you can put these blocks together to create brilliant content, play around with art and come up with great ideas.

The museum hopes that setting the art free will pave the way for many more excellent user experiences—and for art becoming relevant to many more people.10

SMK’s project blog post by Magnus Kaslov on 3D scanning speaks to the philosophical imperative of cultural resource items having expressive life, although it references these in different terms, such as “ghosts,” “aura,” “power,” and “spiritual meaning”:

To return to the quote presented in my introduction, it should be noted that Digital Casts offers a new perspective of one of the key subjects of art and art history: the power of attraction that images exert. The fact that reproductions almost magically retain some of the aura—or ghost, or value, or meaning, or whatever you wish to call it—of what they represent. What the art historian David Freedberg calls “the power of images” in his by now classic book bearing the same title.

Images speak to us, and we want to speak to them. This also holds true of three-dimensional images. We like to surround ourselves with them and to possess them. 3D scans retain some of the traits that fascinate us about the original sculptures. I cannot say exactly what that is, but something very clearly lingers. This trait is not only useful for those who present art—it also adds poignancy to the subsequent existence of these 3D models as they are put to various uses. . . .

He [Julius Lange, First Director of The Danish Royal Cast Collection] didn’t contest that the originals also had their merits which he called sentimental value, the same as the relic had ahead of the cast, but that did not bear on the artistic value. Marble and bronze were beautiful materials, yet the plaster in full reproduced the plastic shape: “from where the work of art gets its spiritual meaning.”11

i.iii The Smithsonian Institution

The 3D Program team, within the Smithsonian Digitization Program Office, has built a corpus of 3D models of cultural resource items across the breadth and depth of the Smithsonian with examples from art, natural history, science and technology, and more.12 It has been working on developing a 3D model program since 2010,13 and in 2013 it hosted the notable Smithsonian X 3D Conference.14 The Smithsonian 3D initiative has contributed to technological development with its open-source 3D viewer and authoring tool suite, Voyager.15 An especially important resource is Smithsonian 3D Metadata Model,16 which furthers the identification of essential data elements in an effort to support greater standardization and interoperability in the field. Regular publishing about the 3D initiative in Smithsonian magazine, Digitization Program Office blog, and other media outlets have provided important updates to educators, enthusiasts, and peer practitioners at other cultural institutions.

In partnership with companies such as Autodesk,17 Google,18 Amazon,19 and others, the 3D program serves as an important digital educational resource for learning in and outside the classroom with augmented reality, mobile, and web browser technologies. The Smithsonian links its 3D imaging digitization practice with the history of cultural resource items reproduction.20 3D models have been used at the Smithsonian to help tell stories of new institutions, like the National Museum of African American History and Culture,21 and commemorate milestones in human achievement with Neil Armstrong’s spacesuit.22

On February 25, 2020, the Smithsonian took an important step to include 3D models as part of its Open Access program.23 As part of the Open Access launch, the Smithsonian made available its 3D data with the glTF open standard developed by The Khronos Group24 and provided CC0 designated models to Sketchfab.25 As the Smithsonian continues to digitize and make available its 3D cultural resource items with more openness, it may better support the potential identified by William Tompkins, National Collections Coordinator at the Smithsonian Institution, who said, “The beauty of this technology is that it does basically put museums together internationally into one global environment.”26

In its 2020 annual report, the Smithsonian Digitization Program Office provided some key findings on the Smithsonian Open Access program with regard to the impact and role of 3D models:

Smithsonian Open Access proved to be a big draw for corporations and foundations who recognized the transformative nature of making millions of collections images as well as 3D models available without restrictions and were eager to partner with us in demonstrating various uses of the Open Access data. 27

Furthermore, “[i]n just the first month after the launch of the Smithsonian’s Open Access Initiative, Smithsonian 3D content was viewed over 400,000 times, and over 40,000 3D models were downloaded.”28

In 2020 the Smithsonian Institution introduced augmented reality Instagram filters built on Facebook’s Spark AR studio as part of its Instagram Stories experience. Collection objects used in this interface were drawn from the Smithsonian’s available pool of 3D models made available as part of its formal Open Access program.

In 2021 the Smithsonian Institution’s Cooper Hewitt Museum’s Interaction Lab presented seven prototypes generated during the Activating Smithsonian Open Access program. The prototypes are all explorable in the browser. The seven finalists received $10,000 each to develop the prototypes. The prototype site documents the selection process, criteria, and judges. Featured prototypes include Art Echo, “a web-based virtual reality experience that reveals the acoustic attributes of 3D objects in the Smithsonian’s Open Access collections while moving through periods of the history of Earth and some of its inhabitants,” as well as Casting Memories, a collection of open, 3D printable recreations of the Benin Bronzes.

Also in 2021, the Smithsonian partnered with The Hydrous and Adobe to create Augmented Reality experiences that explore the ocean’s coral reefs. The immersive experience used the Smithsonian’s Open Access coral scans to allow users to immerse themselves in a bustling coral reef and learn about the threats to coral ecosystems.

i.iii Małopolska’s Virtual Museums

In 2021, Małopolska’s Virtual Museums, a consortium of 48 Polish museums, made available more than 1,000 high-quality three-dimensional models spanning subjects including arms and armor, fine art, engineering, geology, and more. This contribution is one of the largest single contributions to the global commons at one time. Małopolska’s Virtual Museums are breaking new ground and defining new achievements in excellence with the ambition, production rate, and distribution of their global 3D cultural resources. Their contribution shows that a quality 3D model program can be achieved by organizations throughout the world with the serious dedication of personnel, resources, and time.

Most of the models from Małopolska’s Virtual Museums are available in the public domain with the Creative Commons Zero Public Domain Dedication (CC0 1.0). Dedicating 3D models to the public domain with the internationally operative legal tool CC0 enables these cultural resources to be used for a broad spectrum of re-use and remixing applications—even for commercial purposes—without any attribution or legal restriction. Public domain content supports contemporary creators and businesses alike to build new content and experiences without undue burden and limitation. A significant portion of the 3D models from Małopolska’s Virtual Museums include realistically texture and material settings, allowing you to place them directly into the user’s preferred context and setting such as new 3D models, animations, games, movies, and visualizations.

ii. Anatomy of a 3D Model

ii.i Shape

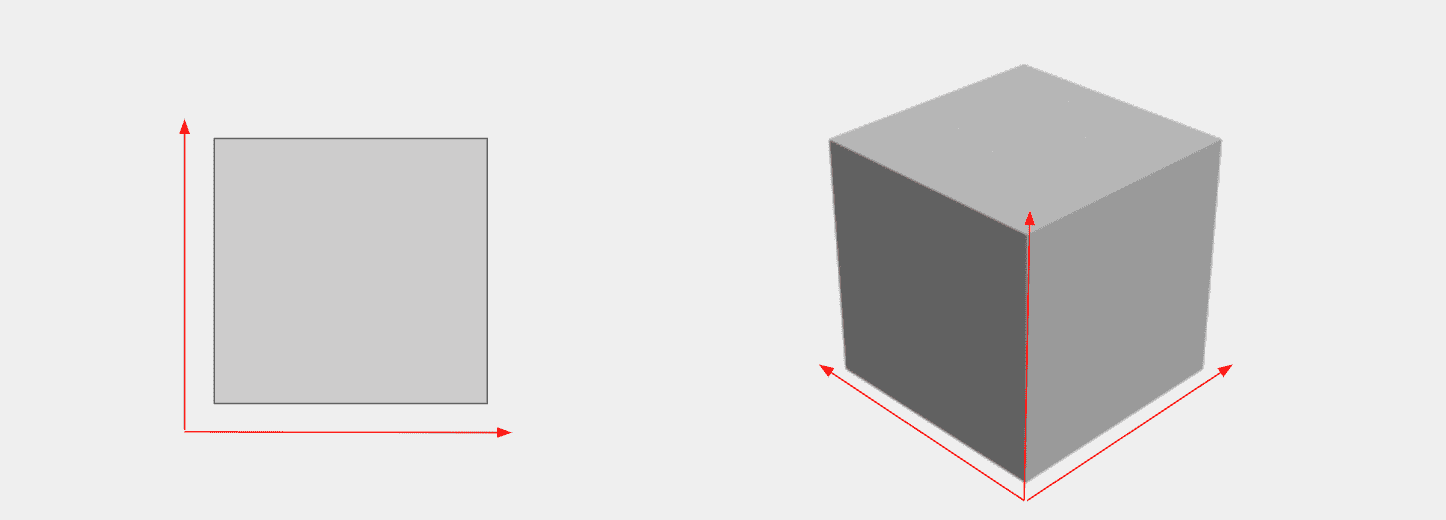

A 3D model primarily differs from a 2D image by the addition of an extra dimension. Pixels in a digital 2D image exist on an X and Y axis (left and right, up and down), pixels in a 3D model can exist on these planes but also the Z axis, (forward and backward/closer and farther away from the viewer).

Illustration of the difference between a 2D image and 3D model, https://help.sketchfab.com/hc/en-us/articles/360017787651-Learning-3D-Part-I-Simple-geometry.

Knowing that we have three axes of movement, we can place a point in 3D space that exists somewhere along each plane of movement. With regard to 3D, we generally call this point a vertex. A 3D model composed exclusively of vertices is known as a point cloud.

Point cloud of St. Alfege Church Greenwich by GreenwichVistaLand, CC BY 4.0

If we join two vertices in different 3D positions with a line, we create an edge.

Joining three vertices, we are able to create the simplest 3D surface: a triangle.

A triangle has a front and a back surface, with the angle direction of the front surface being named the normal. A 3D surface made of four joined vertices is called a quad.

Any surface created by joining five or more vertices is called a polygon, or ngon for short.

Triangles, quads, and ngons are collectively referred to as faces.

By joining and aligning 3D faces, we are able to begin describing 3D shapes from simple pyramids and cubes, all the way up to complex forms like statues, vases, skulls, entire buildings, land masses, etc. These joined up faces are referred to as the mesh, geometry, or surface of a 3D model.

Mammuthus primigenius (Blumbach) by The Smithsonian Institution

As a general rule, the more vertices, edges, and faces used to describe a given cultural resource, the more accurately that form will be described in digital 3D. This is often referred to as the resolution or fidelity of a 3D model. As the resolution of a 3D model increases, so too does the file size and the computational power required to create, capture, and display it in real-time 3D.

Surface Mesh Resolution Comparison by Thomas Flynn, CC BY 4.0

Deciding the output resolution for your 3D model should take into account the intended audience and destination for the data.

ii.ii Color

In addition to describing a shape or form in 3D, a mesh can have (among other things) color information attached to or embedded within it. There are a number of techniques that can be used to add color to a 3D model. They vary based on the original source of the color information, how the color information is attached to specific points on the shape, and how the integrity of the color changes as the model is scaled.

ii.ii.i Vertex Color

One way to color a 3D mesh is to assign a color value to each individual vertex. The color of any connected edge or face is then calculated on a gradient between the joined vertices. This is known as vertex coloring, and a mesh colored in this way is said to be vertex colored. The surface color of a vertex colored mesh is therefore directly linked to the fidelity of the mesh—if you reduce the resolution of the mesh, you reduce the resolution of the surface color information.

Head of Amenhotep III 100k - Vertex Color Only by Thomas Flynn, CC BY 4.0

ii.ii.ii UV Texture Maps

In addition to coloring a 3D face using a blended gradient, it is possible to assign part of a 2D image file to fill the polygon or triangle surface. The method of assigning parts of an image to a 3D mesh surface is called UV mapping. This allows you to create the shape of the object in 3D and then apply a 2D image of the object to give it color and visual texture.

Because the X, Y, and Z axes are already used to describe the 3D geometry, the letters U and V are used to describe horizontal and vertical axes of a 2D image.

To align the 3D surface with the 2D image, certain edges on the mesh are designated seams where faces can be split apart and so flattened and arranged against the image. While this may sound complicated, most 3D capture and creation software calculate UV maps automatically.

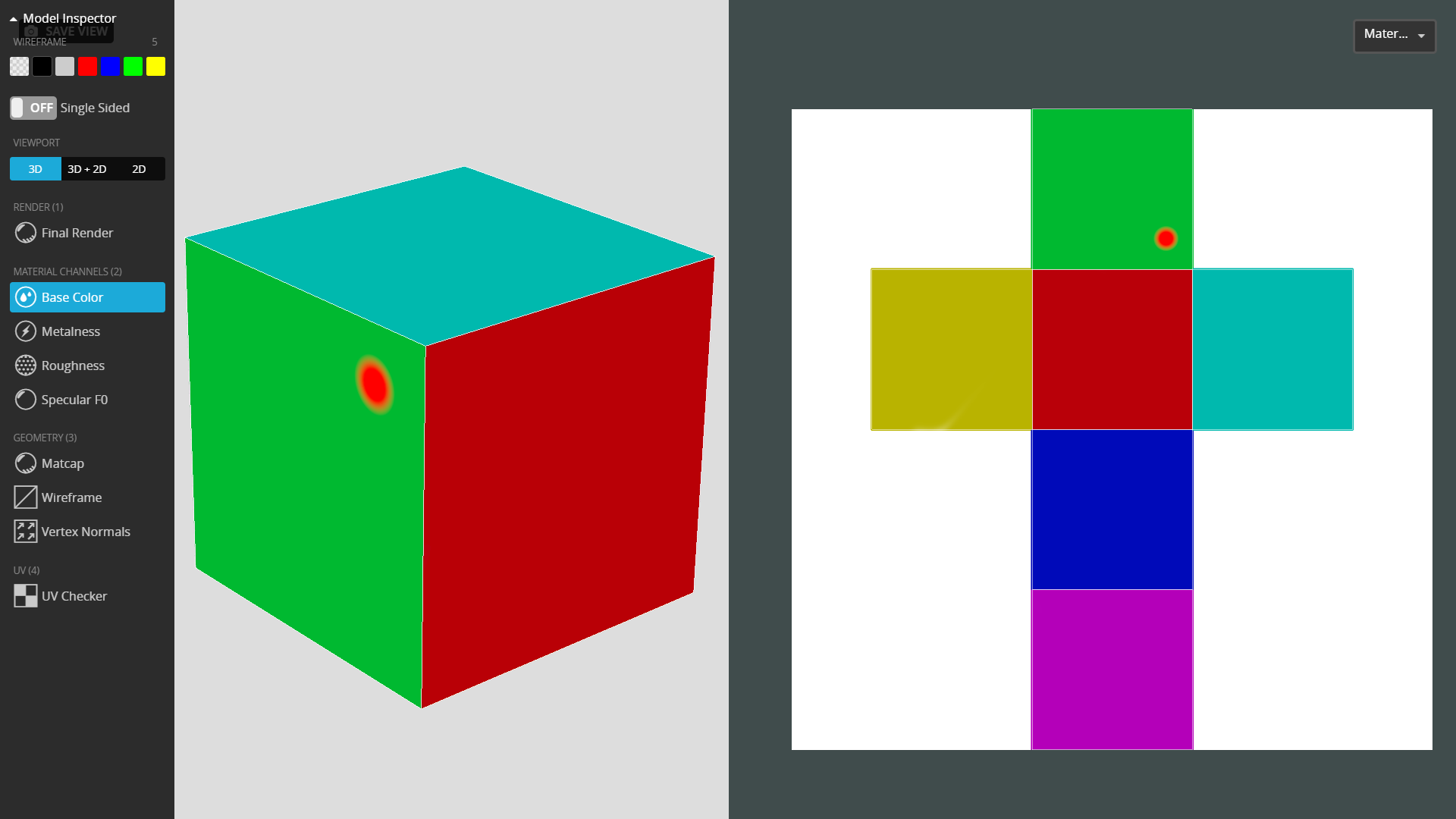

A simple analogy for a UV map is flattening the six sides of a 3D cube:

Cube UV Map Demo by Thomas Flynn, viewed with Sketchfab’s Model Inspector to show the UV mapped image next to the 3D model. The red dot indicates a shared position across both 3D and 2D spaces.

Image maps for 3D models are saved in a 1:1 format and in pixel sizes that are “powers of two”—that is, 128x128 pixels, 512x512 pixels, 1024x1024 pixels, etc. As you might expect, the larger the UV image map dimensions, the higher the number of pixels are assigned to a given 3D face, and the visual resolution is increased. This in turn increases the 3D model’s overall file size and the computational processing power required to render it.

Deciding the output resolution for your UV maps should take into account the intended audience and destination for the data.

Unlike vertex coloring, UV mapping allows a 3D mesh to be colored independently of the mesh’s resolution. This means that a high-resolution 3D mesh can be simplified or decimated—that is to say a given cultural resource can be represented by a mesh with a fewer number of vertices, edges, and faces, while maintaining color fidelity.

Vertex coloring and UV mapping are not mutually exclusive, and the same 3D mesh can include vertex colors and UV-mapped colors which, depending on the 3D renderer, can be combined for the final visual output.

ii.ii.iii Normal and Roughness Map—Specialized UV maps

In addition to coloring the faces of a 3D mesh, there are several other texture maps29 that can have a dramatic effect on the presentation of a 3D model. Two baseline recommended map types are described below, but there are many more that can be created and applied to a 3D model to help more accurately render a given cultural resource.

ii.ii.iii.i Normal Maps

Each face of a 3D model has a surface direction, known as a normal. This direction dictates how simulated light bounces off the surface. If we have simplified or decimated a 3D model significantly during optimization, we can run into the problem that a single face replaces much more complex geometry.

A common remedy for this is to encode complicated surface information from a high-resolution version of our model into a special texture map called a normal map and then map that to the lower-resolution mesh.

3D model Quarter Normal Map RTI by Kevin Falcetano rendered without a normal map…

…and with a normal map. This model is composed of a single quad face.

ii.ii.iii.ii Roughness Maps

Any given cultural resource may include several different surface finishes or be made of several different materials, perhaps with significant differences in how rough or shiny they are. It is not currently possible to easily capture such variation during digitization.

It is possible as part of the post-processing of a 3D model, however, to author a special texture map called a roughness map that can be applied to a 3D model’s UV-mapped surface and show different areas of the surface as having different specular properties. A roughness map is a grayscale image which, depending on the 3D viewer being used, will show darker areas as rough and lighter areas as smooth or vice versa.30

Chrysanthemums by a Stream rendered without a roughness map or simulated lighting.

…the model with a roughness map and lighting applied. Note the reflective highlight now apparent in the areas of gold leaf. The effect is even more apparent when viewed in 3D. It is possible to view an ‘unlit’ version of this embed by using the model inspector.

iii. Common Types of 3D Model

While there are as many types of 3D files as there are applications for 3D, we will now look at types of 3D models most common to cultural heritage applications. Note that we are not talking about file formats just yet, simply the general groups of 3D files you can expect to come across in the wild.

iii.i Mesh + UV Texture Maps

Several 3D file formats support a 3D mesh in conjunction with a linked or embedded image map. Image files either need to be stored alongside the 3D mesh or are embedded in the 3D file itself.

Head of Amenhotep III 5k Colour Texture by Thomas Flynn, CC BY 4.0

iii.ii Untextured Mesh

A 3D mesh without any color data applied is said to be untextured. Untextured meshes are useful in situations in which the color information related to a cultural resource is not of use—for example, in certain methods of 3D printing or when the 3D form itself is what is important. Some 3D capture techniques like X-ray computed tomography (CT scanning) or some structured light scanning will not capture color data at the time of digitization.

Head of Amenhotep III - Surface Model by Thomas Flynn CC BY 4.0

iii.iii Vertex Colored Mesh

The description of this coloring method is covered above, and it is a common output of some types of 3D scanning processes. Typically, any process that involves the capture or computation of colored vertices as part of 3D data production can lead to a vertex colored mesh output.

Head of Amenhotep III 100k - Vertex Color Only by Thomas Flynn, CC BY 4.0

iii.iv Point Cloud

A point cloud or pointcloud is exactly what it sounds like: a 3D model made up exclusively of vertices (points). These kinds of files are commonly an output of LiDAR scanners (often referred to as laser scanners) or photogrammetry software. The vertices in a point cloud can be uncolored or have a color value assigned to them.

Head of Amenhotep III 150k Pointcloud by Thomas Flynn, CC BY 4.0

iii.v Volumetric Data

Volumetric data is less common than surface model data in cultural heritage applications, and it is possible to generate a surface model from a volumetric input using specialized software.

X-ray computed tomography is a scanning technique that is capable of documenting the visible form of a cultural resource, as well as internal structures not visible to the human eye. This technique generates numerous cross-sectionals through a subject using multidirectional x-ray measurements.

The cross-sectional images can be used to generate volumetric 3D data —that is, data that visualizes densities of volume.

Volumetric render of a Gorilla Cranium derived from DICOM files in aleph-viewer.com.

iii.vi Additional features

iii.vi.i Animation

3D models can be animated in several ways. While animating models is beyond the scope of this paper, animation can help better describe how a cultural resource is constructed, functioned, or was used. Animation could also be the only way to record certain cultural performances, such as dance or theatre.

Columbian Press No 3180 by arboo, CC BY 4.0

iii.vi.ii 3D Post-Production—Materials and Lighting

When we talk about “capturing a cultural resource in 3D,” we are most often referring to documenting the physical shape of the resource and possibly the surface color as well. Many cultural resources, however, are made from materials that possess specific physical properties that also contribute to a viewer’s understanding of the resource.

Consider the translucency of a fine marble statue, the colored transparency of a stained glass window, the difference in reflective properties between a wooden walking stick and its polished brass handle. These properties are as much a part of the resource’s nature as its simple shape and color.

At the time of writing, it is not practically possible to capture or record many of the physical traits that differentiate metals from ceramics, glass from paper, etc. during the 3D digitization process. Some of these physical properties can, however, be added by a 3D expert or artist during a post-production phase.31

Decisions should be made during the digitization process that will impact the ease with which these properties can be added. Therefore it is helpful—although not necessarily critical—to consider how you plan to treat these properties during the planning phase.

Understanding of the visible physical properties as described above rely in part upon interaction between viewer perspective and the cultural resource, but also on the lighting environment surrounding both. The same is true when viewing a digital 3D model of a cultural resource that is said to be lit or shadeless, depending on whether or not simulated lighting is present during the digital viewing experience.

Just as in a museum environment, lighting can make a huge difference to how a cultural resource is visually presented, which in turn has an effect on how an object is understood by a viewer.32

An unlit version of the Nefertiti bust by AD&D 4D under a CC BY 4.0 license.

A version of the Nefertiti bust with lighting by AD&D 4D under a CC BY 4.0 license

…the same 3D scene with a simulated lighting environment.

What is the genuine Nefertiti? by AD&D, CC BY 4.0

iv. Common 3D Capture and 3D Creation Techniques and Software

iv.i Capture

Capture refers to the process of recording an existing cultural resource via digitization process.

iv.i.i Photogrammetry

As photography is a method for converting 3D information into a 2D format, photogrammetry does the opposite, converting 2D information back into digital 3D.

This workflow involves first capturing a number of images of a cultural resource from a number of different angles. This can be achieved by moving the camera around the resource itself or placing the resource upon a turntable in front of a static camera. A set of images intended for a photogrammetry workflow can number anywhere from a few dozen up to the many thousands.

You can use almost any kind of digital camera, but the better the images you capture, the better your output 3D model will be.

Photogrammetry software is then able to process the digital image files (JPGs, RAW files) into a 3D model by comparing recognizable points in different images and calculating their position in 3D space using complex algorithms. The points (vertices) can then be used to define a 3D mesh and a color image map can be built from selected parts of the 2D image files.

In general, the more images that are input into and processed by photogrammetry software, the higher the output 3D model and textures will be. Using a higher number of images also requires more processing power or processing time to compute the output 3D model.

Requirements

Digital camera, photogrammetry software, computer hardware (ideally with powerful, dedicated graphics hardware). Little specialist training, working knowledge of photography useful.

Entry-Level Equipment Budget

Camera $300+

Computer $800+

Software $0 (open source); $200+ (commercial)

Outputs

Point clouds, surface meshes, vertex color information, UV image-mapped color information.

Applications

Can capture objects of all sizes from miniature up to entire landscapes.

Limitations

Difficult to capture subjects that are very shiny, transparent, extremely fine (e.g., hair, feathers). Subject scale must be added manually in software.

Commonly Used Software33

iv.i.ii Structured Light

Structured light 3D scanners use specially calibrated projectors and cameras simultaneously projecting and recording a known pattern of lines or grids onto the subject being scanned. Dedicated software then defines a 3D surface model, based upon the distortions in the recorded line or grid pattern made by the subject.

Structured light scanners often exist as dedicated hardware or as a combination of conventional consumer level projectors and cameras. Dedicated hardware systems benefit from known levels of capture accuracy. Some capture scenarios also involve using additional scanning targets.

Requirements

Dedicated structured light scanning hardware OR digital projector(s) and camera(s), structured light scanning software, computer hardware (ideally with powerful, dedicated graphics hardware). Little specialist training.

Estimated Entry-Level Equipment Budget

Handheld Scanner $5,000+

Computer $800+

Outputs

Surface meshes, vertex color information, UV image mapped color information, scale.

Applications

Capturing small-to-medium-sized objects.

Limitations

Attempting to scan very large objects generally results in the creation of unusable amounts of data. Color data capture is generally inferior to photogrammetry.

Commonly Used Structured Light Scanners

iv.i.iii LiDAR / Laser Scanning

Laser scanning hardware is most often used in building information modeling (BIM) to record spaces and architectural scale features. Essentially, laser scanning works by firing a laser from a central unit and recording the 3D position of any surface it strikes, based upon how long the reflected light takes to return to the base station.

Requirements

Laser scanning base station, computer hardware (ideally with powerful, dedicated graphics hardware). Some specialist training.

Estimated Entry-Level Equipment Budget

LiDAR Scanning Unit $5,000+

Computer $800+

Outputs

Color or monochrome point clouds, scale.

Applications

Architecture and landscape scale subjects where accurate measurements are essential.

Limitations

No surface or UV mapped color capture, generally not suitable for smaller objects.

Commonly Used Hardware34

iv.i.iv X-ray Computed Tomography

Commonly used in medical and scientific fields.

Requirements

Dedicated x-ray tomography machine, specialist training.

Entry-Level Equipment Budget

X-ray CT Scanning Machine $350,000 - million+

PC Computer $2,000 - 10k+

Outputs

Density, scale, 2D image sets from which 3D surface models can be derived.

Applications

Very-small-to-medium-size objects, especially where measurements and internal structures are of interest.

Limitations

No surface color information, scan size limited by x-ray machine volume/portability of subject.

Example X-Ray CT Setups

AN15 ES Flat Panel Detector</span>

YXLON Access Y.100 + 450kV, 0.4mm Focal Spot X-Ray Tube and PerkinElmer XRD 1621

iv.i.v Motion Capture

As the name suggests, motion capture is a digitization technique for capturing movement, most often that of human beings (e.g., full body, facial, hand motion). Traditionally this technique has required studio spaces with specialized cameras and tracking targets attached to the human performers. More recent developments in depth-sensing cameras and even smartphones are making motion capture a much more accessible technology.

Entry-Level Equipment Budget

\(-\)$$$ Dedicated Setup

$-$$$ Rental

Requirements

Motion capture studio or stage, bodysuits and targets, specialized cameras, computer hardware (ideally with powerful, dedicated graphics hardware). Specialist training.

OR

Depth-sensing camera, computer hardware (ideally with powerful, dedicated graphics hardware), some specialist training.

Outputs

Motion capture data.

Applications

Full body, facial, hand. and object motion recordings.

Limitations

No 3D model capture.

Example Motion Capture Setups

digitalartsonline.co.uk/news/motion-graphics/how-do-3d-motion-capture-using-iphone-x-camera

iv.ii 3D Reconstruction and Creation

In addition to 3D scanning of a cultural resource, another way to generate 3D content is to engage a 3D artist to create it from scratch. This method is especially applicable to any cultural resource that is “unscannable,” no longer exists or was destroyed, or never existed in the first place—e.g., a fictional space or object.

Authoring—as opposed to capturing—3D models is an entirely different skill set to 3D scanning, and an expert 3D artist often will have studied their craft at a higher education level or have self taught their skills through years of practice.

Several sub-disciplines of creative work are applicable to generating 3D models for cultural heritage.

iv.ii.i Modeling

3D modeling is the process of creating a three-dimensional representation of a surface or object by manipulating faces/polygons, edges, and vertices in simulated 3D space. Just as Adobe Photoshop and MS Paint are software programs used to create 2D art, 3D modeling software allows users to make art that can be explored in three dimensions.

Typical subjects for a modeling workflow include inorganic structures, architecture, industrial subjects, houseware, furniture, and mechanical structures.

Commonly Used Software

The Parthenon Rebuilt by Myles Zhang, CC BY 4.0

iv.ii.ii Texture Painting

Once a 3D model has been created, an additional (sometimes essential) stage in production is to apply realistic colors and materials to the geometry. All texture maps (i.e., color, normal, roughness) can be digitally painted onto a 3D mesh, whether a 3D scan or something that has been created by a 3D artist.

Texture painting makes use of the UV mapping color method described previously and outputs an image file to be associated with a 3D model.

Commonly Used Software

Polychrome Relief Depiction of Ma’at by IPCH Digitization Lab, CC BY 4.0

iv.ii.iii Sculpting

As the name suggests, 3D sculpting is the process of manipulating a 3D object as if it was made out of a material similar to clay. You can push, pull, smooth, grab, pinch, and edit a 3D object to be whatever you’d like.

Typical subjects for a sculpting workflow include organic forms, animals, plants, insects, artistic sculptures, fabrics, and people.

Commonly Used Software

The Punishment- A study of Farnese Hercules by Deepak C C, CC BY 4.0

iv.ii.iv Voxels

A creation popularized by the videogame Minecraft, voxel-based 3D modeling uses visible 3D cubes or blocks (voxels) to build a 3D form. Voxel-based creations can be built “block by block” or existing meshes can be converted to a voxel form using a 3D editor. By no means useful for scientific study or hyper-realistic reconstructions, voxel-based 3D models can still be used to engage with wide-ranging audiences, especially younger crowds.35

A voxel workflow can be used to create 3D representations of most subjects. but the output is generally highly stylized as a result of the nature of this creative technique.

Commonly Used Software

Gumusler Monastery by sundai, CC BY 4.0

v. Quick Start 3D Digitization Guide

As a word of warning, be careful when using this “let’s just go ahead and capture some 3D and publish it” approach—you may unwittingly be laying a potentially unstable foundation for your organization’s 3D digitization program. Be mindful of how you share your project with your colleagues and in public as people new to the concept will often derive their opinion of 3D digitization and its potential benefits and shortcomings based upon your work.

You should also be aware that any time spent on a project will inevitably generate some form of technical and skill “debt”—i.e., commitment to processes and workflows based on the fact that they exist and are seen as the easiest option. This could make it difficult to change and adapt digitization workflows as required once proper planning is undertaken.

v.i 3D Capture Workflow

The cheapest and most accessible 3D capture workflow available to you is most likely photogrammetry. The input data are digital images and the required software runs on most computer hardware, with the caveat that on older and less powerful hardware, you will likely have to wait a lot longer for a 3D output to be processed. It is recognized that this suggested technology chain may still be unaffordable to some organizations.

v.i.i Camera

Your personal digital camera or smartphone camera are likely good enough for a test project.

Tested.com hosts a good “photography for photogrammetry” guide.

v.i.ii Software

Here’s a list of free photogrammetry software, with system requirements and official tutorials for each option. It is highly recommended that you review and consider the potential ongoing costs of using commercial software.

**[Meshroom](https://alicevision.org/#meshroom)**

Open source, Win/Linux. By far the most user-friendly open source photogrammetry software.

- System Requirements

-

Commercial, free version limited to 50 images, Win. The only non-time-limited free commercial software listed here.

- System Requirements

-

Commercial, free trial, Win/Mac/Linux. One of the most commonly used photogrammetry software, 30-day time limited trial.

- System Requirements

-

Commercial, free trial, Win only, cloud-based processing.

- System Requirements

- Official Tutorials

v.i.iii Computer Hardware

Initially you can simply try running one or all of the suggested software applications on your existing computer hardware. If you find that installing the software does not work or processing takes too long or frequently fails, then it might be time to consider investing in something new, basing your purchase on the system requirements in the software section.

v.i.iv Publishing

See the Choosing an Online 3D Viewer section for hosted and self-hosted options

vi. Made with Open Access

The following are examples of experiences made with content from 3D Open Access programs. These experiences themselves may not meet Open Access requirements as defined in this publication in Section 2. Still, a vibrant ecosystem of non-open content made with Open Access is one result of a successful Open Access program.

New content made with Open Access programs that itself is not Open Access, while more limited in its capacity for unrestricted reach, reuse, and scale by the broadest possible user base, can directly benefit users, institutions, and their partners, especially for educational or sponsorship purposes. A ‘made with Open Access’ content development approach might especially be relevant in the context of a cultural institution working with a company to produce a product or service as part of a mutually beneficial commercial arrangement. The creation of new closed access content by using Open Access content, in-line with the source materials specified terms, is a legitimate and viable use of Open Access policies and content.

3D models produced by institutions or third-parties can find their way into remixes and new forms of cultural production. These creations can take any number of forms. The category and concept of “Made with Open Access” acknowledges and documents the hybrid and mixed states of 3D experiences based on Open Access sources due to diverse content development needs, licensing terms, and copyright statuses. An Open Access policy that supports the growth, inclusion, and development of CC0 and CC-BY 3D models, when institutional priorities and resources are able to be dedicated to such purposes, is an important signal to other institutions who have not yet begun their Open Access journey to keep moving forward in their efforts.

vi.i Les Dieux Changeants

Lucio Arese produced a computer graphic imagery movie Les Dieux Changeants using 3D Models, done by Jonathan Beck and the Scan the World initiative, of plaster casts from The National Gallery of Denmark (Statens Museum for Kunst; SMK) on MyMiniFactory. This is an example of a remix of institutionally sourced 3D scans that have been used to make a new and thoughtful work.

vi.ii Sketchfab and Spatial

In 2022, Sketchfab and the immersive social platform Spatial announced direct import of models from Sketchfab to Spatial. This allows Spatial users to create virtual spaces populated by open access 3D models from collections hosted on Sketchfab.

vii. Other

The European Commission tasked the Expert Group on Digital Cultural Heritage and Europeana with developing guidelines for 3D cultural heritage assets. In 2020 they release 10 principles to help guide that process.

IN 2025 GLAM 3D Co-Author Thomas Flynn wrote about the importance of authentic 3D models, especially in a world of AI-generated alternatives. In addition to discussing the importance of authenticity, Flynn explained why GLAM institutions should take active steps to champion their high quality, well optimized models.

Notes

-

Cleveland Museum of Art, Open Access, (December 28, 2018), https://www.clevelandart.org/open-access ↩

-

Cleveland Museum of Art, Museum Policies, (February 14, 2014), https://www.clevelandart.org/visit/ visitor-information/museum-policies ↩

-

Maddie Armitage and Howard Agriesti, Looking From All Angles: ArtLens Exhibition Embraces Photogrammetry, Medium (August 8, 2019), https://medium.com/cma-thinker/ looking-from-all-angles-artlens- exhibition-embraces-photogrammetry- d2cb75d61735 ↩

-

Rijksmuseum, Sharing Is Caring, http://sharecare.nu/, last accessed April 16, 2020. ↩

-

SMK—National Gallery of Denmark in Copenhagen (Statens Museum for Kunst), Digital Casts, https://www.smk.dk/en/ article/digitale-casts/, last accessed April 16, 2020. ↩

-

Merete Sanderhoff, Scanning SMK, One Sculpture at a Time, Medium (August 29, 2019), https://medium.com/smk-open/ scanning-smk-one-sculpture-at- a-time-8e72196219fd ↩

-

SMK—Statens Museum for Kunst @SMK—Statens Museum for Kunst—MyMiniFactory, https://www.myminifactory.com/users/ SMK%20-%20Statens%20Museum %20for%20Kunst, last accessed December 16, 2019. ↩

-

SMK2 Presents: Digital Casts—A 3D Model Collection by SMK—National Gallery of Denmark (@smkmuseum), Sketchfab, https://sketchfab.com/smkmuseum/ collections/smk2-presents-digital-casts, last accessed April 16, 2020. ↩

-

Magnus Kaslov, Ghost in the Scan—3D Scans of Casts in the SMK’s Collections, Medium (March 1, 2017), https://medium.com/smk-open/ ghost-in-the-scan-3d-scans-of-casts- in-the-smks-collections-79560f895369 ↩

-

Maja Ravn Blichmann, SMK Open: Art Wants To Be Free, SMK—National Gallery of Denmark in Copenhagen (Statens Museum for Kunst) (April 30, 2019), https://www.smk.dk/en/ article/art-wants-to-be-free/ ↩

-

Magnus Kaslov, Ghost in the Scan—3D Scans of Casts in the SMK’s Collections, Medium (March 1, 2017), https://medium.com/smk-open/ ghost-in-the-scan-3d-scans- of-casts-in-the-smks- collections-79560f895369 ↩

-

Smithsonian 3D, Smithsonian Digitization Program Office, https://3d.si.edu/, last accessed April 16, 2020. ↩

-

Matt Alderton, Digitization, Documentation, and Democratization: 3D Scanning and the Future of Museums, Redshift by Autodesk (February 23, 2016), https://www.autodesk.com/redshift/ digitization-future-of-museums/ ↩

-

Joseph Stromberg, Watch: The World’s 3D Experts Converge at the Smithsonian X 3D Conference, Smithsonian Magazine (November 13, 2013), https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian- institution/watch-the-worlds- 3d-experts-converge-at-the-smithsonian- x-3d-conference-180947682/ ↩

-

Smithsonian Voyager, Smithsonian Digitization Program Office, https://smithsonian.github.io/dpo-voyager/, last accessed April 16, 2020. ↩

-

Smithsonian 3D Metadata Model, Smithsonian Digitization Program Office, https://dpo.si.edu/index.php/ blog/smithsonian-3d-metadata-model, last accessed April 16, 2020. ↩

-

Autodesk Powers 3D Explorer for Smithsonian Institution, Autodesk (November 13, 2013), https://investors.autodesk.com/news-releases/ news-release-details/autodesk-powers- 3d-explorer-smithsonian-institution ↩

-

Marc Bretzfelder, Google Expeditions AR Brings Smithsonian 3D Models into the Home and Classroom via Augmented Reality, SI Digi Blog (September 14, 2018), https://dpo.si.edu/index.php/ blog/google-expeditions-ar-brings-smithsonian- 3d-models-home-and-classroom- augmented-reality ↩

-

Ewer with Birds, Snakes and Humans, National Museum of Asian Art, AWS Sumerian. https://56bfe6d67d7c4e04a6ab2152540a7e44 .us-west-2.sumerian.aws/, last accessed April 10, 2020. ↩

-

3D Scanning: The 21st-Century Equivalent to a 19th Century Process, Smithsonian Digitization Program Office, https://dpo.si.edu/blog/ 3d-scanning-21st-century-equivalent- 19th-century-process, last accessed December 16, 2019. ↩

-

Explore NMAAHC Collections in 3D, 3d.Si.Edu, https://3d.si.edu/video/ explore-nmaahc-collections-3d, last accessed December 16, 2019. ↩

-

Armstrong Spacesuit, 3d.Si.Edu, https://3d.si.edu/armstrong, last accessed December16, 2019. ↩

-

Effie Kapsalis, 21st-Century Diffusion with Smithsonian Open Access, Smithsonian Open Access Updates (February 25, 2020), https://www.si.edu/openaccess/ updates/21st-century-diffusion ↩

-

Khronos and Smithsonian Collaborate to Diffuse Knowledge for Education, Research, and Creative Use, Khronos Group Press Release (February 25, 2020), https://www.khronos.org/news/ press/khronos-smithsonian-collaborate- to-diffuse-knowledge-for-education-research- and-creative-use ↩

-

Thomas Flynn, Sketchfab Launches Public Domain Dedication for 3D Cultural Heritage,_ _Sketchfab Community Blog (February 25, 2020), https://sketchfab.com/blogs/ community/sketchfab-launches-public-domain- dedication-for-3d-cultural-heritage/ ↩

-

Smithsonian X 3D—Digitizing Collections, Smithsonian Digitization Program Office (November 13, 2013) 1:11-1:20, https://youtu.be/_TiHTkK5Wrs?t=71 ↩

-

2020 Annual Report, Smithsonian Digitization Program Office at 6, https://dpo.si.edu/sites/ default/files/resources/ OCIO%20DPO%20Annual%20Report% 202020-PRINT_version.pdf ↩

-

2020 Annual Report, Smithsonian Digitization Program Office at 3, https://dpo.si.edu/sites/ default/files/resources/ OCIO%20DPO%20Annual%20Report% 202020-PRINT_version.pdf ↩

-

Further map types are described and demonstrated at Materials (PBR), Sketchfab Help Center, https://help.sketchfab.com/ hc/en-us/articles/ 204429595-Materials-PBR, last accessed April 16, 2020. ↩

-

This type of image can often be incorporated into visual descriptions designed to provide details to low vision and blind users. ↩

-

Dale Utt III, How to Create Materials and Textures for Photogrammetry, Sketchfab Tutorials (November 15, 2019), https://sketchfab.com/blogs/ community/how-to-create-materials- and-textures-for-photogrammetry ↩

-

Copy Culture: Sharing in the Age of Digital Reproduction 203 (Brendan Cormier ed., 2018), https://vanda-production-assets. s3.amazonaws.com/2018/06/15/ 11/42/57/e8582248-8878-486e-8a28 -ebb8bf74ace8/Copy%20Culture.pdf ↩

-

Cultural Heritage User Survey 2019, Sketchfab (August 2019), https://docs.google.com/presentation/ d/1avExQtbfl6vDCFyo5VgSyBy638BjdDTAIhw79ClHT5A/ edit#slide=id.g5e4c799188_0_419 ↩

-

Cultural Heritage User Survey 2019, Sketchfab (August 2019), https://docs.google.com/presentation/ d/1avExQtbfl6vDCFyo5VgSyBy638BjdDTAIhw79ClHT5A/ edit#slide=id.g5e4c799188_0_450 ↩

-

See e.g., Manuel Charr, How Museums Are Using Minecraft to Gamify Learning Experiences, MuseumNext (July 17, 2019), https://www.museumnext.com/article/ minecrafting-the-museum ↩